Marty Levine

September 20, 2021`

The stress that COVID-19 has placed on the US economy and our system of governance has made it harder to ignore the glaring flaws in our economic and political systems. If we are willing to look, we can see the failure of the marketplace solutions to societal problems that we have been asked to rely upon. We can see the lie of trickle-down economics and the fallacy that the marketplace ensures fairness and equality. We can see that allowing too much wealth to accumulate in too few hands corrupts and harms. We can see this when we look at our nation’s struggling efforts to build a system we can all thrive in. From childcare to health care, we can see a system where the marketplace does not work.

Child Care is critical to those who use it and to those who earn their livings providing it. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently captured the inability of the silent hand of the market to meet this essential need in stark terms: “Childcare is a textbook example of a broken market.”

In a recently released Treasury Department report, the details of that failing were spelled out. “Several market failures help explain why the current system is unworkable. First, parents are asked to pay for childcare when they can least afford it. Parents of young children often have little work experience, and most people earn higher incomes as they spend more time in the labor force and their careers progress. Some parents have other major expenses, like mortgages or student loans. And, even though most families’ incomes and savings increase as their children age, they are unlikely to be able to borrow against their future savings to cover the costs of care for young children. This is an example of what economists describe as liquidity constraints, a classic market failure, which argues in favor of government support. Second, the spillover aspects of providing children with a high-quality early educational experience – what economists call “positive externalities” – also argue in favor of government subsidies for childcare expenditures. Finally, since the vast majority of the workers are women and disproportionately women of color, the sector likely benefits from existing discrimination in labor markets. This does not suggest that childcare providers are at fault but is an indication of just how untenable the economics of the industry are.”

The marketplace leaves workers under-rewarded; families struggling to find and pay for quality care and children underserved. Under the extreme stress of the pandemic, the system is cracking. According to a recent report by the National Association for the Education of Young Children that the Washington Post cited in a recent story “more than a third of child-care providers are considering quitting or closing down their businesses within the next year, as a sense of hopelessness permeates the industry…Over half of minority-owned centers are in danger of shutting…”

Like childcare, we have a flawed national approach to ensuring that affordable health care is available to all. As the pandemic surged, it was clearly in everyone’s interest to ensure that those who were sick could get treated if no other reason than they would not continue to be infectious and spreaders of a deadly disease. For health care providers and health insurers, this presented the need to choose between their profitability and the public good. Many initially chose the public good and waived many charges that they normally would pass on to their patients and so eliminated barriers that might prevent the sick from getting needed care.

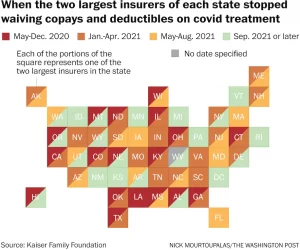

But in a market-based world, this is their choice, and we are now seeing how the marketplace works. As COVID abated, we were learning to live with COVID over the long haul. Insurers no longer saw a PR benefit from doing the right thing and saw a pile of money they were leaving on the table. Profits won out. As the Washington Post put it, “most insurers have reinstated co-pays and deductibles for covid patients, in many cases even before vaccines became widely available. The companies imposed the costs as industry profitsremained strong or grew in 2020, with insurers paying out less to cover elective procedures that hospitals suspended during the crisis… Last year, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 88 percent of people covered by private insurance had their co-pays and deductibles for covid treatment waived. By August 2021, only 28 percent of the two largest plans in each state and D.C. still had the waivers in place, and another 10 percent planned to phase them out by the end of October, the Kaiser survey found. Its survey this year of employer-sponsored plans reflected similar patterns.”

In our months of responding to this hopefully once-in-a-lifetime challenge, we have also seen robust government action work where the marketplace cannot. We have seen that Government can over-ride selfish interests, interests that are comfortable with being favored by the marketplace. The emergency programs that were put in place have worked. They were able to save millions and millions of households from hunger, falling into poverty, and death.

So now we face the critical question of why won’t we learn from this experience and make the systemic changes that will provide for our common welfare? Why won’t we recognize that we don’t have to allow the marketplace to run wild? Consider that “if you’re fortunate enough to live in Vermont or New Mexico, for instance, state mandates require insurance companies to cover 100 percent of treatment. But most Americans with covid are now exposed to the uncertainty, confusion, and expense of business-as-usual medical billing and insurance practices — joining those with cancer, diabetes, and other serious, costly illnesses.”

We need to not only recognize that the marketplace is the wrong approach to building an equitable society, but that it has produced a broken system of governance, one where money buys power. And this purchased power allows those who benefit from the broken status quo to become the ones who are preventing the change we need.

This is so clear in the current battle over the Biden Administration’s struggle to pass its $3.5 billion package of programs designed to take on some of these glaring failures. As the New York Times recently reported, “ Joe Manchin, the powerful West Virginia Democrat who chairs the Senate energy panel and earned half a million dollars last year from coal production, is preparing to remake President Biden’s climate legislation in a way that tosses a lifeline to the fossil fuel industry — despite urgent calls from scientists that countries need to quickly pivot away from coal, gas and oil to avoid a climate catastrophe.”

At a moment systemic change is so clearly needed to ensure that we both have energy and save the planet from self-destruction, it is the self-interest of those who can buy power that appears to be in control. “The most powerful climate mechanism in the budget bill — and the one that Mr. Manchin intends to reshape — is a $150 billion program designed to replace most of the nation’s coal- and gas-fired power plants with wind, solar and nuclear power over the next decade. Known as the Clean Electricity Performance Program, it would pay utilities to ratchet up the amount of power they produce from zero-emissions sources, and fine those that don’t.”

Last week the pharmaceutical industry was able to use its wealth to keep a House Committee from including provisions permitting the US Government to bargain on our behalf with drug companies and lower drug costs. As described by Senator Sanders in remarks reported by The Hill, “What the pharmaceutical industry has done, year after year, is pour huge amounts of money into lobbying and campaign contributions … the result is that they can raise their prices to any level they want…The pharmaceutical industry spent $171 million on lobbying through the first half of the year, more than any other industry, to deploy nearly 1,500 lobbyists, according to money-in-politics watchdog OpenSecrets.”

Money buys access and power in the halls of Congress and it also buys access to the offices where policy, rules, and regulations are made. If the government is to fix the problems that it has allowed the market to create it will need to fix a broken tax system. Yet, according to the New York Times, “the largest U.S. accounting firms have perfected a remarkably effective behind-the-scenes system to promote their interests in Washington. Their tax lawyers take senior jobs at the Treasury Department, where they write policies that are frequently favorable to their former corporate clients, often with the expectation that they will soon return to their old employers. The firms welcome them back with loftier titles and higher pay, according to public records reviewed by The New York Times and interviews with current and former government and industry officials.” The result is the rich keep avoiding paying their fair share.

As accounting firms struggled to change an IRS ruling that would require some of their clients to pay billions of dollars in taxes, one accountant switched sides and began to work for the Treasury Department. “Ari Berk, a tax lawyer for Deloitte, among the leading designers of the tax shelters…left Deloitte’s Washington offices and moved a few blocks west to work for the Treasury. His assignment was to oversee the regulations he had just been pushing to water down. In January 2017, Mr. Berk’s office issued new regulations… The most important change mirrored what Mr. Berk had sought…eight months earlier. That June, Mr. Berk returned to Deloitte. He had been gone barely a year and was immediately promoted to partner.”

COVID-19 has shown us the United States at its worst and at its best. It has shown us that government can make life better and it has shown us a government that turns it back on those at risk and makes their lives even harder. It has shown us what we can accomplish if special interests are not allowed to keep control. And it has shown us how disastrous the voices of special interests, particularly the interests of the rich and powerful can be.

In choosing how we go forward we can choose to keep going as we are, relying on an approach that we know will leave many behind, which will ignore the needs of those without wealth and power. Or we can choose a new direction, one that is focused on easing the problems that inequality has caused. We can do this not because new directions based on a different set of principles are guaranteed to work perfectly, but because we choose to base on efforts on a different foundation. As we approach midterm elections next year this is the choice we will be making.