Marty Levine 10/29/21

This is what systemic racism looks like:

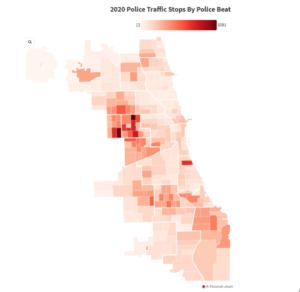

It is a map of Chicago. It is a map of where Chicago Police made a total of 327,224 traffic stops in 2020. The map, based on data collected by the Illinois Department of Transportation and analyzed by Block Club Chicago, shows us graphically that if you live in a Black community, you are much more likely to be pulled over by the Chicago Police than if you live in a white neighborhood. And if you live in neighborhoods where Chicago Policemen and women, themselves, live you stand the least chance of being hassled.

Digging deeper into the data, Block Club Chicago found that even in white, favored neighborhoods, Black drivers were singled out for differential enforcement. “Even in predominantly white neighborhoods and areas where there were comparatively fewer traffic stops, Black drivers were disproportionately stopped, the data shows. That disparity holds true for the enclaves where many Chicago police officers live, like the neighborhoods in the 16th and 22nd districts.”

And this is what systemic racism sounds like. Alderperson Nick Spasato who represents a predominantly white ward was asked by Block Club Chicago to comment on this map. “The lack of stops…isn’t because cops aren’t enforcing traffic rules in neighborhoods where many officers live. Residents in his ward rarely get stopped because ‘this is a very law-abiding community,’ Sposato said. ‘When you get pulled over, anybody can get out of a ticket. All you have to do is cooperate with the police…White people just know how to talk their way out of a ticket. They just cooperate.” (emphasis added)

The staff of another Alderperson who represents one of the favored communities, Anthony Napolitano, told Block Club that the “massive disparities in stops are not due to bias in how traffic rules are enforced. Residents in Black neighborhoods get stopped more because more violations happen in those areas…residents rarely violate traffic rules due to a profound respect for the rule of law…I am a lifelong resident of the 41st Ward. What I love about our ward is that it is filled with hard-working families that love their community, their neighbors, and have a profound respect for the rule of law. Your data highlights these facts, as would the documented 911 calls for service in the 41st Ward compared to other parts of the city…”

Napolitano’s explanation of traffic stops echoes the failed “broken windows” strategy of policing that emerged in the 1980s, an approach that took a concept that was based on building community safety on a strong bedrock of community trust and partnership into a statistical game of making large numbers of arrests for minor offenses with the mistaken belief that this would limit more serious crime. It forgot that community trust was the most necessary ingredient and it failed.

“Broken Windows” policing emerged from the work of criminologist George Kelling. But, as reported by Frontline’s Sarah Childress in 2016 “Kelling has since said that the theory has often been misapplied….Kelling told FRONTLINE that over the years, as he began to hear about chiefs around the country adopting Broken Windows as a broad policy, he thought two words: “Oh s–t! You’re just asking for a whole lot of trouble. You don’t just say one day, ‘Go out and restore order.’ You train officers, you develop guidelines. Any officer who really wants to do order maintenance has to be able to answer satisfactorily the question, ‘Why do you decide to arrest one person who’s urinating in public and not arrest [another]?’ … And if you can’t answer that question, if you just say ‘Well, it’s common sense,’ you get very, very worried. So yeah, there’s been a lot of things done in the name of Broken Windows that I regret.”

Chicago Police may not have gotten this message nor recognized the bias of their actions. Despite well-worded denials of bias by top CPD officers, the message does not seem to have been translated into action. Community Policing Director Glen Brooks said in a 2018 PBS interview that traffic enforcement was indeed a targeted action, a strategy for cracking down on more serious crime. “When we have communities experiencing levels of violence, we do increase traffic enforcement,” Brooks said. “We are trying to do anything humanly possible to curtail the violence.”

Systemic racism reflects a built-in bias. It does not need or mean every police officer is a bigot. But every police officer is working within a system that sees Black people as dangerous, prone to crime, and needing to be dealt with harshly.

Remel Terry, vice president for the Chicago West Side Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and a lifelong West Side resident captured the impact of this pattern of bias in her comments to Block Club. “You have people who are being pulled over, but you don’t see the crime-stopping, People are like, ‘If you have all this time and energy to pull folks over, then why aren’t you able to do other things like actually be present to stop crime from being committed?’ The over-policing of Black communities on the South and West sides is a major reason why there is a “wedge in that trust” between residents and the police…The trust does not exist. It has never existed. This is part of why it does not exist because you can have people who consider themselves law-abiding citizens … who too often have experienced being pulled over for no reason and being ticketed unfairly…”

This is what systemic racism looks like and sounds like. Unless we recognize this, stop denying it. Stop fighting over distractions like Critical Race Theory in our schools and look at pictures like this. Otherwise, we are doomed to continue scratching our heads because things just are not going to get better