Marty Levine

March 13, 2022

Last week, in his first State of the Union address, President Joe Biden felt that among all of the other challenges our nation and the world faces it was important to call out the need for more funding for our police forces. “That’s why the American Rescue Plan that you all provided $350 billion that cities, states, and counties can use to hire more police, invest in proven strategies. Proven strategies like community violence interruption — trusted messengers breaking the cycle of violence and trauma and giving young people some hope. We should all agree: The answer is not to defund the police. It’s to fund the police. Fund them. Fund them. Fund them with resources and training. Resources and training they need to protect their communities.”

In this moment, when we are faced with a Russian invasion of Ukraine, are in the third year of a once in a century pandemic, with inflation threatening the economic viability of more families, with the very essence of our democracy threatened, and with the government unable to create a sense of common purpose and a way forward is police funding really such a priority?

Despite the way some in the news media and in the world of politics tell the story, we are not living in the middle of a huge crime wave and, overall, crime is not at an unprecedented level. The situation is more nuanced and complex than that. Consider this recap of the available data from the Council on Criminal Justice (emphasis added):

- “During the first half of 2021, homicide rates remained above the levels seen during the same period in prior years. The number of homicides rose by 16% compared to the first half of 2020 (an increase of 259 homicides) and by 42% from the first half of 2019 (an increase of 548 homicides.)) Even with the 2021 increase, the homicide rate for the cities studied was well below the rate for those cities in the early 1990s (15 deaths per 100,000 residents versus 28 murders per 100,000 in 1993).

- Aggravated and gun assault rates were also higher in the first half of 2021 than in the same period of 2020. Aggravated assault rates increased 9%, while gun assault rates went up by 5%. Motor vehicle theft rates were 21% higher in the first half of 2021 than the year before.

- Other major crimes declined. Robbery (-6%), residential burglary (-9%), nonresidential burglary (-9%), larceny (-6%), and drug offense (-12%) rates dropped from the same period in 2020.”

Lois Beckett and Abené Clayton, writing for The Guardian last summer described the complexity of crime in our nation, “what’s happening with homicides is not part of some broader ‘crime wave.’ In fact, many crimes, from larcenies to robberies to rape, dropped during the pandemic and continued to fall during the first few months of 2021. “Crime” is not surging. Even the broader category of “violent crime” only increased about 3% last year, according to the preliminary FBI data from a large subset of cities. It’s homicide in particular that has increased, even as other crimes fell.”

It is not as if we are not already spending a lot of money on policing. The most current data available from the US Census Bureau is for 2019; in that year State and Local governments reported spending more than $123 billion. That budget supports more than 1 million state and local law enforcement personnel. Digging deeper, “even as the 50 largest U.S. cities reduced their 2021 police budgets by 5.2% in aggregate—often as part of broader pandemic cost-cutting initiatives—law enforcement spending as a share of general expenditures rose slightly to 13.7% from 13.6%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg CityLab. And many cities like Minneapolis and Seattle have watered down or put on pause changes that were proposed or even passed at the height of the 2020 demonstrations against racism and police brutality.”

And this does not account for how states and cities responded to President Biden’s direction last summer to divert COVID relief funds to augment local police forces. “We’re now providing more guidance on how [state and local governments] can use the $350 billion nationally that the American Rescue Plan has available to help reduce crime and address the root causes…cities experiencing an increase in gun violence were able to use the American Rescue Plan dollars to hire police officers needed for community policing and to pay their overtime.”

But the present system does not work very well; it did not prevent this increase in violent crimes, and it does not solve most crimes effectively. FBI crime statistics for 2020, the last year for which national data is available, shows that only 3.6 million arrests were made in the 7.5 million criminal incidents they gathered data on. That is at best a 48% success rate. In crimes against persons that number falls to just 34%. From my perspective, these are numbers that would indicate we have a very successful approach to solving crime, certainly not an indication that we just need to do more of what we are currently doing.

In the discussion of the need for police reform and abusive policing that followed the murder of George Floyd, we often heard about “bad apples,” the isolated bad cops, and much resistance to the systemic reform those shouting “Defund the Police” were calling for. Earlier this month, A Washington Post study examined the 25 of the nation’s largest police and sheriff departments and found that “within the past decade…more than $3.2 billion” had been spent settling suits arising from Police misconduct. “The Post found that more than 1,200 officers in the departments surveyed had been the subject of at least five payments. More than 200 had 10 or more.”

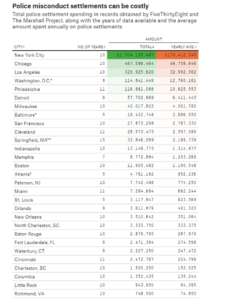

This supports research on police misconduct settlements conducted by Five Thirty Eight and the Marshall Project that found “$2.5 billion over 10 years — was spent by the nation’s three largest cities, which had a combined budget of around $115 billion last year alone. Smaller cities spent much less than New York, Los Angeles or Chicago, although a significant number, including Milwaukee, Detroit and San Francisco, still spent tens of millions of dollars on police misconduct settlements over the same period.”

These “bad apple” settlements are the canary in the tunnel for deep and systemic troubles in our current approach to policing, troubles that erode trust and make police departments part of the problem and not of the solution.

So, if the system is ineffective and if it is problematic is there any reason to believe that just making it bigger will result in safer communities and less violent crime?

I do not think so.

As Charles Blow recently reminded us, President Biden once had a better answer to the problem. When he addressed Congress in February 2021 these were his words, “My fellow Americans, we have to come together to rebuild trust between law enforcement and the people they serve, to root out systemic racism in our criminal justice system and enact police reform in George Floyd’s name that passed the House already.”

The causes of this bump in violent crime are complex. Calling for more money and more police may be politically smart if you are interested in playing to fear. Avoiding the impact of the proliferation of guns may sidestep politically difficult issue will not solve the problem. The impact of COVID-19 has had in disrupting lives may prove to be the match that lit the inflammable tinder of structural poverty and racism, problems that have long been ignored and left festering but will not be touched by the reflexive call for more money.

The frayed relationships between many police departments and the people they are sworn to protect can only have served as an accelerant. These are problems we choose to ignore at our risk. And that is what those who see funding as the missing piece of the puzzle are choosing to do.