Marty Levine

October 7, 2022

It’s nice to see signs of progress. Maybe the arc of the moral universe does indeed bend toward justice. That’s how I felt after taking after looking at the results of a Child Trends study commissioned by the New York Times, Lessons From a Historic Decline in Child Poverty, that was reported out last month.

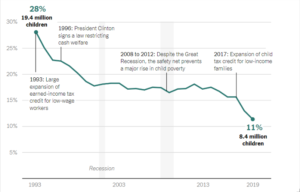

The study’s introductory paragraph tells us of the steep change in the arc that has influenced the lives of so many young Americans. “The past quarter century witnessed an unprecedented decline in child poverty rates. In 1993, the initial year of this decline, more than one in four children in the United States lived in families whose economic resources—including household income and government benefits—were below the federal government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) threshold. Twenty-six years later, roughly one in 10 children lived in families whose economic resources were below the threshold. This is an astounding decline in the child poverty rate, which has seen child poverty reduced by more than half (59%; see figure below). The magnitude of this decline in child poverty is unequaled in the history of poverty measurement in the United States.”

As important as the results they reported is Child Trends’ analysis of what forces were behind this progress. Did we see such dramatic improvement because more parents went to work and the overall economy boomed? Or was it the result of local, state, and federal government efforts to strengthen our safety net policies and fund them more robustly?

According to the researchers, the “…social safety net was responsible for much of the decline in child poverty from 1993 to 2019, cutting poverty by 9 percent in 1993 and by 44 percent in 2019—tripling the number of children protected from poverty over this time.

“In 1993, the social safety net (within which we include federal tax and transfer programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC) cut poverty by 9 percent compared to what it would have been without the safety net. In great contrast, in 2019, the social safety net cut child poverty by 44 percent. Over that time, the number of children protected from poverty by the social safety net more than tripled, from 2.0 million children in 1993 to 6.5 million children in 2019.

“The two programs that experienced the greatest growth in the percentage of children protected from poverty were the EITC (Earned Income Tax Credit) and housing subsidies.”

This finding is critically important because as a nation we have continued to battle over whether poverty is a personal failing or if it is an outcome systemic, a result of flawed policies. Those who see it as a personal failure, of a lack of willingness to work hard enough, have advocated for limiting government assistance. Conservative Republicans and neo-liberal Democrats have shared a belief that work is the magic bullet to ending the scourges of poverty.

They have advocated for work requirements as an essential ingredient to even minimal levels of public assistance. They have posited that the safety net itself was the problem. In 1996, President Bill Clinton was very clear that this was his belief when he told the nation “When I ran for President four years ago, I pledged to end welfare as we know it. I have worked very hard for four years to do just that. Today Congress will vote on legislation that gives us a chance to live up to that promise, to transform a broken system that traps too many people in a cycle of dependence to one that emphasizes work and independence, to give people on welfare a chance to draw a paycheck, not a welfare check. It gives us a better chance to give those on welfare what we want for all families in America, the opportunity to succeed at home and at work. For those reasons, I will sign it into law.”

Thirty years later Republican President Donald Trump’s Budget Director Mick Mulvaney mirrored Clinton when he explained his administration’s approach to safety net policies. “There’s a dignity to work, and there’s a necessity to work to help the country succeed. We are no longer going to measure compassion by the number of programs or the number of people on those programs. We’re going to measure compassion and success by the number of people we help get off of those programs and get back in charge of their own lives.”

The analysis completed by Child Studies tells us that this thinking is wrong. Without even the fragmented and still insufficient network of public policies that have been put in place to lift poor children out of poverty, even in an era of a robust economy with strong job growth, millions of children would be living through the life-changing harms of poverty.

Arloc Sherman, the vice president for data analysis and research at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, pointed out to the Washington Post “that this dramatic drop in child poverty was achieved without work requirements while also being accompanied by widespread voluntary return to work by parents. There was a huge decline in child poverty and a very large increase in parents working year-round without any work requirements. We did not need to require the parents to work.”

Hilary Hoynes, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, was clear about what this study was teaching us, as reported by the NY Times. “We could do a lot better. When we spend money, we make gains. Providing more resources to low-income families changes children’s life trajectories.”

The study shows what we can do if we, as a nation, put our economic muscle behind our efforts and points the way forward. “The social safety net continued to play an important role in protecting children from deep poverty over the past 25 years. However, we saw only minimal growth in the social safety net’s role in reducing deep poverty. The social safety net reduced child deep poverty by 62 percent in 1993 and by 66 percent in 2019.”

The NY Times tells us that this data also shows that “Black and Latino children are about three times as likely as white children to be poor. With the poverty line low (about $29,000 for a family of four in a place with typical living costs), many families who escape poverty in the statistical sense still experience hardship. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, an intergovernmental group, ranks the United States 36th out of 41 countries, defining poor children as those with less than half their country’s median income. But since the United States is unusually wealthy, its poor children may have higher incomes than some nonpoor children abroad. The United States looks better in comparisons that use the American poverty line as a common standard. Yet even with that definition, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2019 found the United States ranked fourth among five richEnglish-speaking countries, trailing Australia, Canada, and Ireland.”

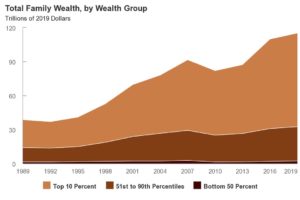

It is interesting to consider the Child Study analysis in the light of another piece of our economic history that was recently shared by the Congressional Budget Office, Trends in the Distribution of Family Wealth, 1989 to 2019. Over these thirty years, as we were able to drive down childhood poverty rates, we were allowing wealth to be concentrated even further. “Wealth became less equally distributed over the 30-year period. The share of total wealth held by families in the top 10 percent of the distribution increased from 63 percent in 1989 to 72 percent in 2019, and the share of total wealth held by families in the top 1 percent of the distribution increased from 27 percent to 34 percent over the same period, CBO estimates. By contrast, the share of total wealth held by families in the bottom half of the distribution declined over that period, from 4 per-cent to 2 percent…CBO estimates that the share of wealth held by the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution increased by 7.4 per- centage points over the period—from 26.6 percent in 1989 to 34.0 percent in 2019.”

That we could drive down childhood poverty while wealth inequality continued to increase speaks to how effective even flawed social safety net programs can be. Clearly, we can do more.

Senator Bernie Sanders tweeted the challenge of all of this data, encouraging and depressing as it is. “This report confirms what we already know: The very rich are getting much, much richer while the middle class is falling further and further behind and being forced to take on outrageous levels of debt,” said Sanders. “The obscene level of income and wealth inequality in America is a profoundly moral issue that we cannot continue to ignore or sweep under the rug. A society cannot sustain itself when so few have so much while so many have so little. In the richest country on Earth, the time is long overdue for us to create a government and an economy that works for all of us, not just the 1 percent.”

We can do this if we look with open eyes for real answers and not for scapegoats. We can do this if we are all willing to share the burden.