An impending divorce spotlights what is wrong with modern philanthropy

Marty Levine

Updated May 7, 2021

It was an announcement heard around the world. Bill and Melinda Gates are ending their marriage and the future of the world’s wealthiest Foundation was in doubt.

That one couple’s marital status could evoke concerned headlines across the world illustrates one aspect of our philanthropic model in an age of individualism and the growth of great personal wealth.

Together the Gates created one of the world’s largest charitable foundations with an endowment currently valued at more than $50 billion. They attracted other mega-wealthy donors who trusted their priorities and their wisdom. They have been able to invest as much as $5 billion annually toward their priorities. With these arrows in their quiver, they gained immense influence as their programmatic priorities and their strategies for change, at a moment when public sector investments in too many areas of basic human need are so badly underfunded, shaped public policy.

The Foundation has played a central role in a range of fields ranging from health care on a global scale to our nation’s educational system. The foundation has developed its approach to the areas it has focused on with limited if any public oversight. Its funders have been able to use their own knowledge and wisdom as a guide.

All of this, for the good and for the not-so-good they may have accomplished, has been controlled by them. So, it is very natural that news that their “them” is to be no longer raised worries among organizations, public and private, that they have partnered with. Perhaps these priorities and commitments would change. Things that were important to them as a couple would be valued differently when they became two individual decision-makers. How the Foundation would operate seemed less certain.

The Gates’ personal issues are of concern because we do not require that giving, that donating means giving or donating. Our laws and policies allow donors to remain in charge of their donations in perpetuity. All the accolades for generosity and all the financial benefits of being a philanthropist are available do not require ceding control of the donor’s wealth nor does it require that funds reach the public who they were supposed to benefit.

This is the legacy that the first generation of mega-philanthropists who created the first generation of charitable foundations, Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford, and their contemporaries spawned. This is the path that our current generation of wealthy men and women are following down with increasing frequency.

Earlier this week James Andreoni, Distinguished Professor of Economics at the University of California San Diego, and Ray Madoff, Professor of Law and Director of the Forum on Philanthropy and the Public Good at the Boston College Law School published a new study, IMPACT OF THE RISE OF COMMERCIAL DONOR-ADVISED FUNDS ON THE CHARITABLE LANDSCAPE 1991-2019, which tries to tease out what the growth of Foundation and Donor-Advised Fund giving has meant to operating charities, the organizations that do the work of helping people at risk.

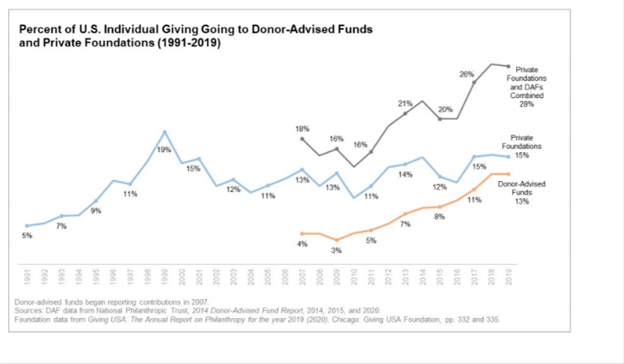

First, they found that 30 years ago, only a small amount, 5%, of the nation’s total annual giving was funneled Foundations and therefore not used directly for a public benefit but “by 2019, 13% was going to donor-advised funds and 15% was going to foundations.” While individual giving has remained largely constant, there has been a substantial shift in this giving toward donations to private foundations and donor-advised funds and away from direct giving to charities.” By 2019 25% of charitable giving was being funneled into in DAF’s and Foundations, publicly sanctioned vehicles that do not require actual and broad-based public direction of how those funds are utilized.

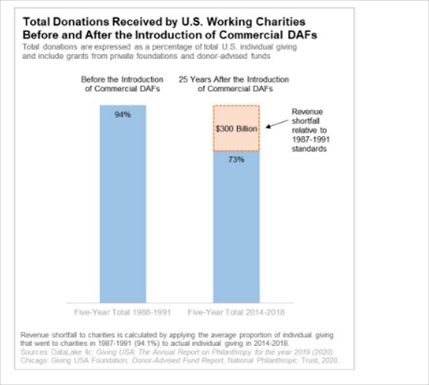

The direct impact of the growing Foundation and DAF sector is that funds being received by operating charities, funds that are immediately available to feed the hungry, provide counseling and do the myriad of other direct services that non-profit, philanthropically supported organizations do. “A comparison of data from 1987-1991 to data from 2014-2018 shows that whereas charities received between 92-95% of individual giving in 1987-1991, in the period 2014-2018 charities only received between 71-74% of individual giving in charitable donations. (This includes donations from private foundations and donor-advised funds, as well as direct contributions.) This represents a shortfall of $300 billion over a 5-year period.”

The ability of singular individuals and couples to have such unilateral power to shape the nonprofit world and to impact public policy is problematic. Author Linsey McGoey,, in comments reported by the Chronicles of Philanthropy captured this danger, “it can really emphasize the volatility surrounding private giving and the fact that private giving is so contingent on the whims of a couple. The fact that we don’t really know the long-term ramifications of this divorce on the foundation just highlights the fact that we are too reliant as a society on the whims of wealthy people when it comes to voluntarily distributing their excess wealth.”

Whether or not there are changes in the Gates Foundation’s funding because of a marital dispute is only an issue because we continue to allow Donors to retain control of their philanthropy. Perhaps this the price we must pay for having those $300 million donated at all. Perhaps the current generation of donors demand that level of control.

Is that a price worth paying? I think not.