Marty Levine

May 24, 2021

What I do not know may not hurt me, but it certainly can hurt others.

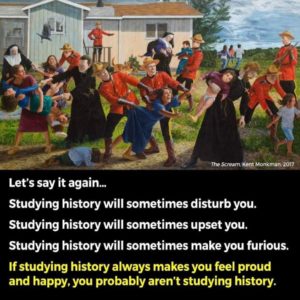

It is one year since George Floyd was murdered and 100 years since the Tulsa Massacre. Two events that are evidence of how deep and enduring our nation’s racism is. Two events that can be seen fully only when looked at through a clear lens that does not filter out white privilege and responsibility. As their anniversaries move past us, there is a national effort to sanitize our history, protect our fragile egos and keep us from having to take responsibility for white America’s legacy.

Across the country, conservative think tanks and legislators are working to teach about a nation that exists only in our fantasies. This is the history that Texas State Sen. Brandon Creighton described to the Texas Tribune that would be mandated when a bill he is sponsoring is approved by the Republican-controlled legislature: “traditional history, focusing on the ideas that make our country great and the story of how our country has risen to meet those ideals.” It is a history that would believe that Tulsa was just a riot and not an organized pogrom perpetrated by white Oklahomans on their city’s prosperous black population. It is a history that would teach that George Floyd’s black skin had nothing to do with his murder.

The bete noir has become “Critical Race Theory.” Kimberlé Crenshaw, a founding critical race theorist and a law professor who teaches at UCLA and Columbia University defined this school of thought in comments reported by CNN, “Critical race theory is a practice. It’s an approach to grappling with a history of White supremacy that rejects the belief that what’s in the past is in the past, and that the laws and systems that grow from that past are detached from it…” Crenshaw further stated that “like American history itself, a proper understanding of the ground upon which we stand requires a balanced assessment, not a simplistic commitment to jingoistic accounts of our nation’s past and current dynamics.”

The Roman historian Livy described history as “the best medicine for a sick mind; for in history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see, and in that record, you can find yourself and your country both examples and warnings; fine things to take as models, base things rotten through and through, to avoid.”

Nothing to be feared, it would seem, from a balanced assessment of our past and our present. Yet the demand to take that deeper look has infuriated the base of the Republican party.

For those who have benefitted from the parts of our history that are “rotten through and through” the desire is strong to blot them out and sanitize them. The move to teach a broader view of our national history will force everyone to confront the ties between our current reality and events that happened generations ago. The fear that something in my life may need to change, that I may need to make atonement for the sins of my fathers and mothers, has aroused a backlash against anything that asks us to remember that troubling reality of “American Exceptionalism.”.

Donald Trump tapped into that fear when he attacked the NY Times’ 1619 Project. “Critical race theory, the 1619 Project and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison, that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together, will destroy our country…” As the Supreme Court had done when it eviscerated Federal Voting Rights legislation in its Shelby County v Holder ruling, Trump seized on a desire to see racism as ancient history, an evil that we have conquered and expunged. He gave moral immunity to those who wished to walk away from their own responsibility and wiped away the unpaid claims of those whose lives remain degraded by the sins of our past.

Across the nation, Trump’s words are now being used to fuel a battle over the curriculums that guide our public schools and colleges. The content of our national history has become a political football.

North Carolina’s State Superintendent Education Catherine Truitt was quoted in a press release as saying that legislation being considered in her state would sanitize our history, “This is a common-sense bill that provides reasonable expectations for the kind of civil discourse we want our children to experience in public schools. This ‘golden rule’ approach ensures that all voices are valued in our school system….Classrooms should be an environment where all points of view are honored. There is no room for divisive rhetoric that condones preferential treatment of any one group over another.”

The euphemism of protecting civil discourse are the code words for squashing a frank look at white privilege in 2021. According to the North State Journal, that North Carolina legislation will expressly prohibit the “promotion of concepts that create discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress for any individual “solely by virtue of his or her race or sex.”

In Idaho, as reported by the Guardian, similar legislation turns these words into a harmful stew of public policy by preventing “teachers from ‘indoctrinating’ students into belief systems that claim that members of any race, sex, religion, ethnicity or national origin are inferior or superior to other groups…[and]…makes it illegal to make students ‘affirm, adopt or adhere to’ beliefs that members of these groups are today responsible for past actions of the groups to which they claim to belong.”

The bill that Texas’ Creighton was advocating teaches America he wishes to remember and strips out existing “requirements to study the writings or stories of multiple women and people of color.” It took opponents of the bill great effort to not have “the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, the 13th 14th and 19th amendments to the U.S. Constitution and the complexity of the relationship between Texas and Mexico “meet the same fate.

The only purpose of this legislation is to keep students, and their parents, from being confronted by their own history, of having to be self-reflective enough to consider questions about their own lives and comforts. In denying that Racism’s tentacles still spread across our nation, these legislative efforts seek to protect the power and wealth of those who are beneficiaries of the past. Or as Trinidad Gonzales, a history professor and assistant chair of the dual enrollment program at South Texas College described it in comments reported by the Texas Tribune, “Giving equal weight to all sides concerning current events would mean that the El Paso terrorist ideology would have to be given equal weight to the idea that racism is wrong. That is the problem, white supremacy would be ignored or given deference if addressed. That is the problem with the bill.”

As with so much in this moment, the effort to protect the status quo, keeping power and wealth undisturbed is well coordinated. In the halls of Congress, in State Houses and local venues across the nation, those pushing the nation in a harmful direction use the same platitudes; they are all singing from the same well-funded hymnal.

Defending our ability to teach a complex, discordant history is about more than our schools. It is about our future as the democracy we claim to be. Historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi described the importance of complexity, “The historian does simply not come in to replenish the gaps of memory. He constantly challenges even those memories that have survived intact.”

Sigmund Freud got it very right: “Only a good-for-nothing is not interested in his past.”