Marty Levine

April 8, 2022

In 2015 the editors of Nonprofit Quarterly published their definition of Philanthropy. “ A Greek term which directly translated means ‘love of mankind.’ Philanthropy is an idea, event, or action that is done to better humanity and usually involves some sacrifice as opposed to being done for a profit motive. Acts of philanthropy include donating money to a charity, volunteering at a local shelter, or raising money to donate to cancer research.”

As a nation we take pride in philanthropists, big and small, contributing $471.44 billion in 2021, a sum that continues to make us the world’s most charitable nation! That this level of giving was accomplished in the year in which the nation was being ravaged by a pandemic made it seem even seem more wondrous.

Yet, if you look a little further into the reality of American philanthropy, there is another, more disturbing story. American philanthropy is increasingly dominated by the “giving” of the wealthiest among us. It is becoming less about humanity and less about sacrifice. While they are honored for their great levels of philanthropy, should we be questioning whether this new generation of mega-donors are really philanthropists?

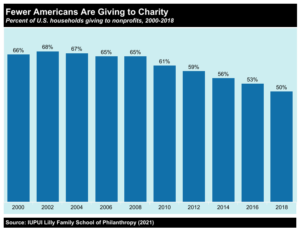

The Institute for Policy Study’s Helen Flannery and Chuck Collins recently highlighted the findings from research from the Lilly School of Philanthropy’s that makes this worry quite real. The latest data from Lily’s “Philanthropy Panel Study revealed that the percentage of U.S. households giving to charity had slipped below 50 percent for the first time since the study began twenty years ago. According to the survey, in 2008, 65 percent of the households surveyed had given to charity. In 2018, just ten years later, that had dropped to 50 percent. The declines in donor participation showed up consistently when controlling for all socio-demographic characteristics.”

More money from fewer givers is not surprising when we remember that over these years the gap between the richest 1% of our population and the rest of us grew to unprecedented levels. The wealthiest men and women among us are able to make staggeringly large donations so that just looking at the nation’s total charitable giving masks the loss of small donors. And the loss of smaller donors is another unfortunate outcome of the growing wealth gap and the increasing levels of economic struggle across the nation. Households struggling to pay their own bills have less ability to give.

The loss of smaller givers has a cost beyond the dollars they represent. As the giving base shrinks, the democratic nature of American philanthropy weakens. As the donor base reflects the nation less and less, it can affect who benefits from philanthropic spending in ways that weaken the fabric of our nation.

Our nation has rewarded charitable giving contributions by making them tax-deductible. As giving concentrates to the wealthiest, they are able to take a greater share of that benefit for themselves, even if they do not need it. “The top 1 percent of income earners in the United States have rocketed from just one-tenth to nearly half of all charitable deductions in just 25 years—allowing them to disproportionately reduce their tax burdens while giving them an outsized voice in what happens to charities.”

This is a shockingly perverse outcome. Men and women who do not need the tax benefit to pay their bills are lessening their tax bills resulting in the government having less funding to shore up our very frayed safety net. Families who are struggling day to day to get by, are left to struggle, hoping that some of those donated funds will help create nongovernmental programs to ease their pain.

Consider that In 2020 the “average annual charity donation for Americans in 2020 was $737.” The gifts of these smaller donors go directly to organizations doing the work of making society better, providing those programs and services that can help men, women, and families at risk. Be their beneficiaries churches, schools, homeless shelters or any other of the tens of thousands of service organizations across the nation that are qualified to receive contributions, these are the organizations providing services to individuals or communities. The money given by small donors is quickly translated into action that benefits people.

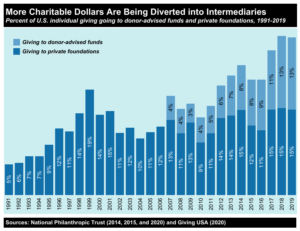

But that is not true of the large donors. Larger givers increasingly park their donations in the foundations and donor advised funds (DAFs) that they control. These are not organizations that are in the day-to-day business of improving lives. While these organizations qualify, under current tax law as charities and while the gifts made to them are tax-deductible, they can park what they can invest rather than spend their resources for some time in the future when the donor may decide they want to use the funds for actions that improve humanity and help people live better lives. They may, at some time in the future, spend those funds in doing the work of societal improvement or they can hold on to it, invest it and watch it grow. While gifts from small donors to the charities of their choice must be used quickly by the receiving organization; large donors are allowed to play by a separate set of rules.

By using Foundations and DAFs, large donors get the financial benefit of immediate tax deductibility and the societal benefit of being seen as philanthropic. At the same time, they do not have to give up any control of how their money is being used. They retain the ability to use their “gifts” as their personal tools for making the societal changes they, and they alone, deem worthy. These are benefits only available to the wealthiest among us.

Small donors can choose which organizations they wish to support but they get little control of how their funds are actually spent. By being one of many supporters their power and influence is limited. They can look at who organizations serve and how they serve them. They can choose organizations that they believe do things well and, in a manner, they believe is correct. But they will have little real control over the organizations they support.

With large giving comes power. The prospect of receiving a large gift is an allure that few if any non-profit organizations cannot help but be affected by. So why is this problematic? As long as they are giving their funds away, as long as at some point money will flow from their foundations and their DAFs to working nonprofits does it really make a difference?

The strings and expectations being imposed by the donor are directly related to the size of the gift. Using their wealth, mega-donors are able to determine these strings and conditions and can steer their beneficiaries in directions that meet their own personal vision of the world. This gives them influence, whether or not they have knowledge and expertise. There is little accountability for how mega-philanthropists exert this influence. If they are wrong, even if they do harm, there are few if any checks and balances and no consequences for the way to wield their money.

This total discretion is dangerous. For every philanthropist like Mackenzie Scott, who is giving away billions with few strings there are many others who place conditions on their giving. For every Mackenzie Scott who is giving to organizations that I think well of and support, there is a David Koch who is supporting organizations I believe are destructive. For every George Soros who supports political goals I support, there is Betsy DeVos whose political giving runs against everything I believe in. But what they all share is the ability to give charitably and politically with little control on how much wealth they can devote to turn policies and practices in directions that they like and that benefit them directly.

Consider the findings in a paper published by researchers at Northwestern University (Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans, Benjamin I. Page, Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright) which looked at the political thinking of wealthy Americans and compared it with available information about the non-wealthy. What they found were significant differences in critical issues like jobs and government support programs. “Gaps between the policy preferences of wealthy Americans and those of other citizens are especially evident with respect to job programs and income support…only a minority of the wealthy…supported any of six ideas or programs we asked about….43 percent agreed with the statement that “Government must see that no one is without food, clothing or shelter,” 40 percent said the minimum wage should be set “high enough so that no family with a full-time worker falls below the official poverty line…” only about one quarter…favored the idea of a “decent standard of living” for the unemployed, and even fewer… wanted to increase the Earned Income Tax Credit… Most striking, given the high importance that the wealthy attribute to the problem of unemployment, is their overwhelming rejection of federal government action to help with jobs. Only 19 percent of the wealthy said that the government in Washington ought to “see to it” that everyone who wants to work can find a job…A bare 8 percent said the federal government should provide jobs…for everyone able and willing to work who cannot find a job in private employment…Among the general public, in contrast, about two-thirds (68 percent) said the government should “see to it” that people can find jobs. “

The inordinate power that large philanthropy bestows on the philanthropist becomes quite dangerous when their values do not reflect the nation as a whole. And when it is possible for these same few individuals to also dominate politics and their ability to make large political donations, we have real danger waiting to pounce. They are able to co-mingle how they invest philanthropically with how they invest politically and coordinate it all with their very personal, profit-making enterprises. And all with little oversite or control.

We have allowed this small class of very wealthy people to become so rich that they can spend billions on their philanthropic and political efforts without any degree of sacrifice. The inequitable distribution of wealth is bad. But when that inequality is turned into this level of power and influence it is plain evil.